Understand Mungo

Mungo Archaeology

Signs from the past

The ancient Willandra people left behind a variety of materials that can help us to understand how they lived, who they were and how they related to the local environment as it changed around them. This material was left mostly by accident, such as waste from food preparation, fireplaces, or stone tools manufacture. Some was more deliberate, such as burials. Most of the archaeological materials are hard and durable including stone artefacts, mineralised bones and fire baked sediments. Plant matter and other soft material has not preserved well in the Mungo environment.

The lunettes are the main storehouses for these archaeological remains. As the windblown sediments gradually piled up, material left on the surface became buried, and the buried material was covered ever deeper. This orderly collection helps to date the artefacts; by studying the layers in which they are found their age can be assessed. Recent erosion, of the Mungo lunette in particular, has brought many long-buried archaeological features to the surface. Other features, such as stone quarries and relatively recent campsites, are sometimes found on the open ground.

It is important to note that ALL archaeological objects are important and protected by New South Wales law. They must not be touched or disturbed. Aboriginal Discovery Tours are a great way to learn about local archaeology out in the field.

Stone artefacts

Stone is the most durable of all natural materials, and is naturally scarce around the Willandra Lakes. Apart from the white nodules of calcium carbonate that lie scattered around by nature, most other rocks you see in the area are likely to be human artefacts.

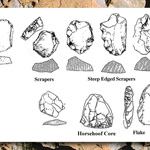

These may include recognisable stone tools such as points, knives, hatchets or axes, and grindstones. But by far the most common pieces of rock are waste flakes and cores, left over from knapping, a term used to describe the manufacture or maintenance of flaked stone artefacts. There are large quantities of flaked stone spread over the Willandra landscape, and indeed across most landscapes in Australia, especially in the inland - which gives some measure of how long Aboriginal people have been living here and working stone.

A scatter of waste flakes often indicates a campsite where people worked on tools, or knapped flakes from a core to use straight away - flakes are sort of throwaway knives, they can have razor sharp edges and can be used immediately but often break or become blunt. Stones that have been deliberately knapped show tell-tale features that are readily recognised by a trained eye. A whole branch of archaeology is dedicated to studying and classifying stone tools to learn about ancient technologies and how they changed through time and in different places.

Aboriginal people used stone tools for a huge variety of purposes. Large flat grindstones were used to grind grass and other seeds into a flour that was then made into damper. Points were used for spear tips. Knives were essential for butchering game and making wooden tools. Scrapers were used for shaping wood and cleaning skins. Hatchet or axe heads were ground to a sharp edge, and were used to remove bark from trees. Stone was a vital and highly valued resource for hunter-gatherers, and was widely traded.

Stone tools cannot usually be dated directly, but sometimes their age can be determined from their association with fireplaces or where they lie in the layers of sediment. In rare cases a tool may carry microscopic residue of organic material, such as flesh or plant matter.

So where did all this stone come from in a landscape of sand and clay? Some of it is local but much also comes from far away. Good flaking stone needs to be hard and fine-grained and to fracture smoothly. Various silica-rich rocks are ideal and were sometimes traded across large distances. The local Willandra stone is silcrete, a kind of fossil soil cemented together with silica in a natural process of water leaching. Layers of silcrete outcrop in places in the lakebeds, and most of these outcrops show signs of extensive quarrying by the ancient Willandra people.

Stone hatchets or axes from this area were brought in from elsewhere. Analysis of the stone has shown many hatchets in western New South Wales originated from axe quarries in central Victoria, some 400km to the south of Mungo.

Middens

Middens are the remains of meals, usually many meals. On the Australian coast, piles of discarded shells can be very extensive and many metres in height.

At Willandra, the accumulated remains of shellfish, fish, yabbies and mammals have all been found. By the fact that they are burnt, or of a consistent size, or otherwise arranged in ways that could not have happened naturally, archaeologists can usually tell if they were left by humans. Shells can naturally accumulate along old lake beaches, for instance, but they will be mixed sizes, not burnt and often broken and worn by wave action.

Freshwater animals found in the middens include Golden Perch (Macquaria ambigua), Trout Cod (Maccullochella macquariensis), yabby (Cherax destructor) and a freshwater mussel (Velesunio ambiguus). All of these species are still found in the nearby Darling, Murray, Murrumbidgee and Lachlan rivers.

Organic remains can be directly dated using radiocarbon analysis, and of course they tell us what the people were eating. Plant remains have generally not survived, but the ancient Willandrans had a varied meat diet including fish, freshwater mussels, and many small mammals including four types of bandicoot, three rat kangaroos, three hare wallabies and native rats.

Fish and shell fossils are particularly useful because they can provide a lot of information. One of the most common fish fossils are small bones from the ear called otoliths. These grow throughout the fish's life in concentric rings and can reveal not only how old the fish was but something of the chemistry of the water in which they were living, such as the salinity level.

Fireplaces

Fireplaces are so fundamental to human experience that they invoke special feelings. It can be very moving to stand over an ancient hearth where a family of ice age hunter-gatherers warmed themselves and cooked their meals beneath the same bright outback stars that we see today.

Three kinds of ancient fireplaces are found at Willandra. Very thin horizons of charcoal from burnt wood and ash are one type. Another is a bed of clay comprised of clay lumps that have been baked and used as a heat retainer and fire-bed. The third, and most common form of fireplace is made from the capping of termite nests. Termites in this area make their nest underground, and the only surface indications are a small, shiny and bare circle of sediment, approximately 1m diameter. The capping on these nests is very hard and it was often broken into pieces and used in fireplaces as a heat retainer and fire-bed. Fireplaces survive well when buried in the sediments, and charcoal can be directly dated - provided it has not been contaminated with more recent carbon washed down from above.

Clay hearths have another special quality - they preserve a record of the alignment of the Earth's magnetic field at the time when they were baked. In this way a major shift in the Earth's magnetic field about 30,000 years ago was first discovered at Lake Mungo. The Lake Mungo Geomagnetic Excursion, as it is known, has since been confirmed at other locations around the world.

Burials

Burial places of their ancestors hold a special significance for Aboriginal people who put great importance on being laid to rest in one's own Country. A large number of human remains have been discovered at Mungo, but few excavations of ancestral remains have been undertaken since the three traditional tribal groups became more involved in archaeological decisions.

Mungo Lady and Mungo Man are of world heritage significance because of their great age (42,000 years) and sophisticated burial rituals. Much has been learnt from their remains.